Learn to navigate USDA hardiness zones and how to protect plants from frost and wintery conditions both in and outside their planting zones (USA hardiness map included).

![]() This article is also in audio form for your listening enjoyment. Scroll down just a bit to find the recording.

This article is also in audio form for your listening enjoyment. Scroll down just a bit to find the recording.

Each type of plant has a preferred set of growing conditions and tends to grow where those conditions are suitable. If a seed lands in a spot with the wrong conditions, the plant may start to grow, but will be at a disadvantage to other established species, which usually results in the seedling dying.

Gardeners want to grow a wide selection of plants, and they only have one location to grow them all in. Granted, even in a small garden, some areas are wetter and others drier, and some get more sun than others, but for the most part, each of us has one set of growing conditions, and our selected plants must adapt to them.

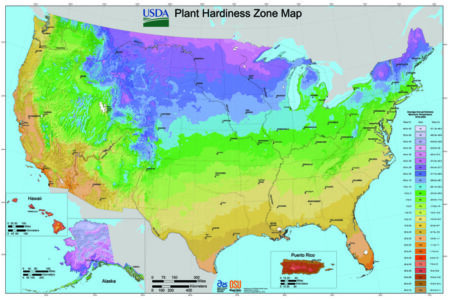

Let’s take a closer look at planting zones (USA map below) and how plants adapt to various environmental growing conditions.

Planting Zones: USA Garden Hardiness Map

Hardiness zones, also known as “gardening zones” and “growing zones,” are a set of numeric designations that identify a narrow set of climatic conditions. Most of these systems are based on the average annual lowest night temperature. So, for example, Zone 5 has a lowest night temperature of minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit.

The original system was developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which uses averages of the lowest night temperatures. Each zone represents a 10-degree increment (see map, above).

North America has 13 zones, with the lowest number indicating the coldest region. These zones are further divided into 5-degree increments using the letters “a” and “b.” For example, Zone 10a is 5 degrees cooler than Zone 10b. Generally, nurseries don’t bother labeling plants with “a” or “b.”

Each plant is also assigned a hardiness zone range to match the conditions where the plant will grow.

Many plants do poorly in zones that are too warm, because they’re not equipped to survive high temperatures or different levels of precipitation. Gardeners should select plants that include their zone within the range in the catalog or on the packet or label.

Much of online plant-hardiness information is based on the U.S. system, so knowing the U.S. zones is useful, even if your country has its own system. If you’re purchasing local plants in countries other than the U.S., make sure you know which system they use for labeling plants.

Limitations of Hardiness Zones

Hardiness zones are useful for selecting plants, but they have limitations. Cold-hardiness isn’t the only important criteria. Hydrangea macrophylla grows in Zones 4 through 9, so it grows in my Zone 5 garden. However, this plant blooms on the previous year’s buds, and the buds are only hardy to Zone 6. So although the plant grows where I live in Ontario, it rarely flowers, because the buds get killed off in winter.

Creeping phlox (Phlox stolonifera) is hardy in Zones 4 through 8. It’s advertised as being an evergreen groundcover, but it’s really only evergreen in Zone 6 and higher.

Hardiness of woody plants is also affected by “provenance,” which indicates where seed was collected. Redbuds grown from local seed are hardy here, but redbuds grown from seed collected in Zone 8 produce plants that aren’t hardy here. Provenance is rarely indicated on plant tags, and many plants sold in colder climates are produced in warmer climates.

Testing Planting Zones in the USA

If you search the internet, you’ll soon realize that commercial sites don’t agree on a plant’s hardiness. Values can be all over the map. The one site I trust most is Dave’s Garden.

When a new plant is brought to market, it doesn’t have a zone designation. The breeder can guess based on similar plants. A new tulip cultivar probably has the same hardiness as other tulips, but what about a new hybrid from parents with different zones?

One way breeders establish a plant’s hardiness zone is to grow it in various climatic conditions, and the All-America Selections Display Gardens are one way to do this. These gardens are located in various zones in North America and host the testing of new plants. After a few years of growing in test gardens, we gain some understanding about a plant’s hardiness, and over time, our knowledge grows.

Gardeners are also important for fine-tuning hardiness zones. I tried growing the South African thistle (Berkheya purpurea) from seed even though it was listed as a Zone 7 plant. It seems hardy in Zone 5. Until gardeners try growing some of these warmer plants in colder conditions, we won’t know whether they’ll grow.

Dealing with Cold

Cold temperatures limit plant growth, especially below freezing, but plants have learned to adapt. Some plants have no problem growing in the Arctic.

So, how do plants cope with the cold? The answer depends on whether the plant is herbaceous or woody.

Herbaceous plants’ stems and leaves die back when conditions become unfavorable. Their underground structures are protected from cold by the soil and by the dry vegetation they drop. This vegetation traps snow around the crown, keeping plants warmer. It’s one reason gardens shouldn’t be cleaned up in fall.

Woody plants go through a hardening-off process where soft, green growth becomes hard, woody material that’s much less affected by cold. Deciduous woody plants lose their tender leaves.

Soil Is a Heat Source

Step outside in winter and inspect your poor garden. How can those perennials survive when everything is frozen? The secret lies in the center of the Earth. The heat from hot molten lava travels up to the surface, making the soil itself a heat source.

If you touch the surface of the soil, it’s frozen and feels cold. Soil loses heat quickly to air and wind. However, the soil is quite a bit warmer even a couple of inches below the surface. Soil does freeze, but it doesn’t get much colder than the freezing point. The roots and other plant structures are much warmer than you think.

This heating effect of soil is dramatically increased when it’s covered with mulch, fall leaves, or, better still, snow. New fluffy snow is about 95% air, making it as good an insulator as plastic foam or fiberglass. Snow traps heat under it, keeping the soil warm. It also prevents wind from blowing heat off the surface of the soil. Many plants will survive winter under snow but die without it.

Preventing Frost Damage

Pure water freezes at 32 degrees. As ice forms, its crystals are sharp enough to rip cells apart, and this damage harms plants more than the cold. So how do plants make it through a cold winter?

To understand this, you first have to know a bit more about freezing water. We say water freezes at 32 degrees, but that’s only true for pure water. Water that contains solutes (other chemicals) will freeze at a lower temperature. The water in your car doesn’t freeze in winter, because it contains antifreeze. The sugars, proteins, fats, and minerals in plant cells all act like antifreeze and lower the temperature at which the cellular liquid freezes.

All of these liquids will finally freeze at some temperature. This freezing point will depend on the concentration of solutes in the water. Plants take advantage of this phenomenon by reducing the amount of water in their cells as winter approaches. Less water means a higher concentration of solutes and a lower freezing point.

Plants also use a trick called “super-cooling,” which prevents ice crystals from forming even when temperatures are below freezing. When all of these tricks are combined, plants can withstand a temperature of about minus 40 degrees without freezing, and that’s plenty to keep most plants alive.

A few woody species experience temperatures below this and still survive. They use an additional technique where they move water out of cells into the spaces between cells, and while the water will form ice there, it won’t damage living cells.

Protecting Plants from Frost

The most important thing a gardener can do to protect plants from frost and other wintery conditions is to buy hardy plants. If you buy hardy plants, there’s no need to wrap them. If you bought the wrong tree, there might be things you can do to keep it alive, but why do that to yourself and the tree? Additionally, keep gardens well-watered. Even after leaf drop, roots are still actively growing and need water.

Here are some other things gardeners can do to protect their plants in the cold. Your climate will dictate whether any of these is required.

Wrapping trees. People wrap trees to keep them warm, often using burlap on evergreens or bubble packing plastic on container plants. These wrappings don’t protect plants from cold.

Cold is the absence of heat, which is the energy stored in moving molecules. The only way to warm something that’s cold is to provide heat.

You can add heat in a few ways. If the sun shines on clear plastic, it will warm the inside and the ice will melt. If you’re wrapping a container sitting on the ground, you can get heat from the soil, but to make this work, the bubble wrap will need to go right to the ground. If you only wrap the top, there won’t be a heat source, and the plastic will do nothing to keep the plant warm.

Another technique is sinking that container into the soil so the pot is covered. This is how I overwinter all of my potted plants.

What about wrapping an evergreen with burlap? Again, there isn’t a heat source, so this won’t keep the plant warm. It might reduce wind, which reduces water evaporation, but burlap doesn’t provide warmth.

The other reason for wrapping evergreen trees is to prevent damage from snow load or ice buildup. Some vertical conifers, such as junipers, are prone to this kind of damage, and the burlap keeps the branches close together and prevents snow or ice from bending them down. A better solution is to select trees that don’t have this problem, such as pines and spruces.

Mounding soil. This used to be a common practice for roses, but it’s used less these days, because very hardy roses are available.

Soil is mounded around the plant in late fall and then removed in spring. In a semi-hardy rose, the woody parts and dormant buds under the soil will survive winter, and those above the soil will die off. It’s a bit of work, but it’s effective.

Rose cones. Rose cones are plastic-foam boxes placed on top of roses to keep the rose warmer in winter; it’s the modern equivalent of mounding soil.

While the plastic foam won’t prevent low temperatures, it will prevent sudden drops in temperature, and if the crack between the bottom of the cone and soil is sealed with soil, it’ll keep the plant warmer.

Rose cones help if you buy roses that aren’t hardy, but buying hardy roses is better.

Mulch. Mulch adds insulation above the soil and keeps belowground structures warmer. It also slows the evaporation of water from the soil, and this may benefit plants more than the extra warmth.

Some argue that mulch freezes and then keeps the soil cold longer in spring than soil that’s not mulched. This is true. But what’s better, frozen soil or warmer soil? The answer is, it depends.

For landscape plants, keep the ground frozen longer. You don’t want it to warm up and get the plant growing only to experience a late frost. Instead, keep plants dormant a bit longer. If they flower a week later, it’s no big deal.

Vegetable gardens are different, especially in cold climates where the growing season is already short. In this case, remove the mulch as soon as possible in spring to allow the sun to warm the soil. Many seeds and seedlings want warmer soil.

When I grow garlic from a clove I cover the the plants with straw in late fall to trap extra heat in the soil so roots keep growing as long as possible. They stay covered all winter. Then, as early as possible, I remove the straw so the sun can warm the soil and get the shoot growing. I’m trying to extend the growing season so they make larger cloves. Then, in late spring when the soil is warm, I put the straw back to stop weeds and to reduce watering needs.

Whitewashing trunks. Winter sunscald happens in colder climates. The sun heats up the bark during the day, followed by a sudden drop to low temperatures at night. Rapid temperature changes cause cell damage in the bark, which results in the bark splitting. Most of the damage is found within a few feet of the ground.

Various wraps around the trunk, whether paper, plastic, or white paint, reflect sunlight and therefore keep the bark from getting too hot. Wraps will also hold in some warmth at night to limited effect.

Brown-colored paper wraps actually absorb heat and can increase the temperature of the bark. Only white or silver products reduce temperature extremes.

Wraps should be removed in spring. Painted surfaces can be left alone.

Robert Pavlis has been an avid gardener for more than four decades. He’s the owner and developer of Aspen Grove Gardens, a 6-acre botanical garden that features over 3,000 varieties of plants. Specializing in soil science, he has been an instructor for Landscape Ontario and is a garden blogger, writer, and chemist. He teaches gardening fundamentals at the University of Guelph and garden design for the City of Guelph, Ontario, where he currently resides. This is excerpted from his book Plant Science for Gardeners (New Society Publishers).